What happened at O’Hare

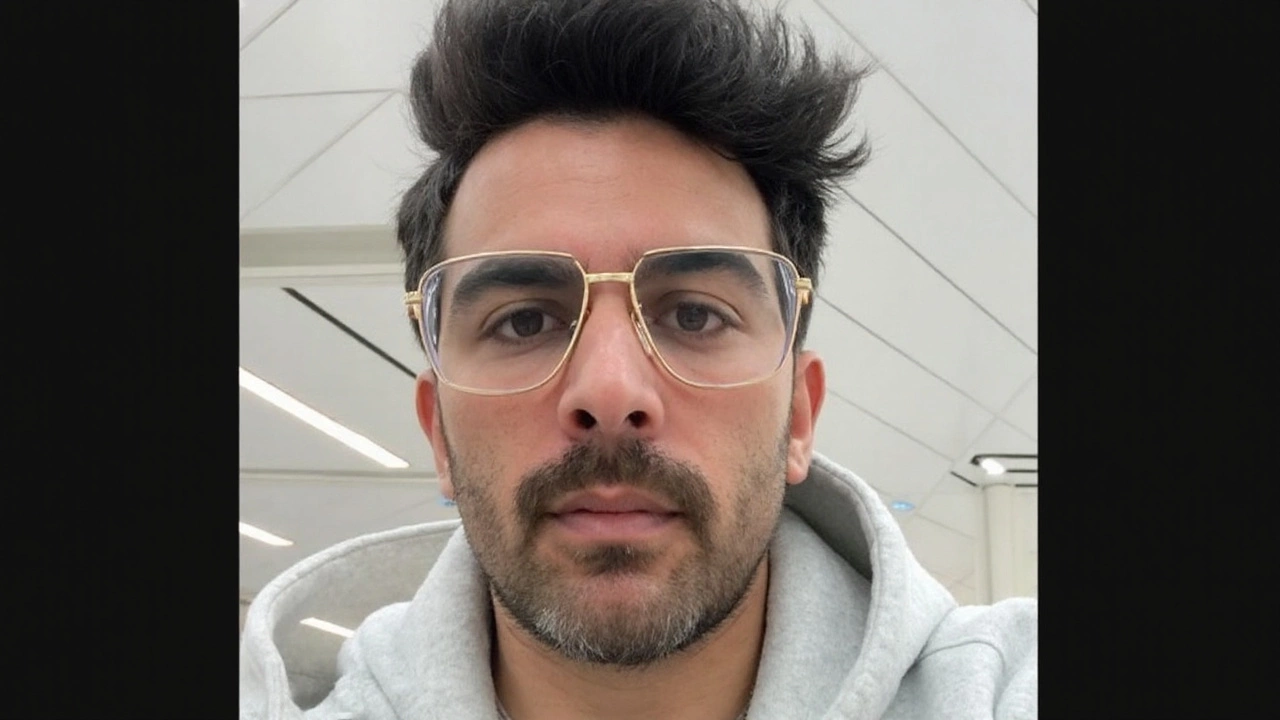

Two hours at a U.S. border can feel like forever. For Hasan Piker, it turned into a political fight. The Turkish American Twitch star and political commentator says U.S. Customs and Border Protection pulled him aside at Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport on Sunday, May 12, and grilled him at length about his views on President Donald Trump and Hamas. He was coming back from a family trip to Paris and headed to speak at the University of Chicago.

Piker, 33, is a U.S.-born citizen and a member of Global Entry, the trusted traveler program that’s supposed to speed you through customs if you’re considered low risk. He told his audience in a 40‑minute YouTube and Twitch breakdown that officers diverted him from the Global Entry process, took him to a secondary area, and questioned him about his politics. That, he said, crossed a line: national security screening morphing into an interrogation about lawful speech.

“The government is now officially willing and able to intimidate you for your speech,” he argued in his stream, describing the encounter as meant to chill criticism. He framed the episode as a warning shot to outspoken figures like him who regularly denounce U.S. foreign policy and Israel’s war in Gaza. His point: if a prominent citizen with trusted traveler status can be pressed on political beliefs at the border, who can’t?

DHS pushed back within hours. Tricia McLaughlin, an Assistant Secretary at the Department of Homeland Security, publicly dismissed Piker’s account, saying he was “lying for likes.” Her message was blunt: officers follow the law, not political agendas. CBP labeled what happened a routine inspection and said Piker was promptly released when the process was done.

That clash—Piker’s allegation of viewpoint-based intimidation versus DHS’s insistence it was standard procedure—has set off a familiar debate about how far border agents can go when citizens reenter their own country, and whether political speech is getting swept into a security dragnet.

Piker, who streams to nearly 3 million followers under the handle HasanAbi, has spent months covering the war in Gaza, campus protests, and the 2024–25 election season. He often calls out the administration’s policy on Israel and the U.S. role in the conflict. His O’Hare stop landed the day before a scheduled talk at the University of Chicago—timing that only intensified speculation about whether his prominence, and his views, played into it.

In an interview with Responsible Statecraft, he said he suspects federal officials now fear “blowback” and “bad branding” because the incident reads to many as an attempt to police speech. He emphasized that, as a citizen, he is protected by the First Amendment and that government questioning about political beliefs at the border should raise alarms even for those who disagree with him.

CBP, for its part, didn’t budge. The agency’s stance has been consistent for years: secondary inspections are lawful, and agents can ask a wide range of questions to determine admissibility and identify risks. Even Global Entry members can be pulled aside, and membership doesn’t guarantee a frictionless entry every time.

The bigger picture: border powers vs. free speech

Here’s the uncomfortable truth about the U.S. border: agents have broader search and questioning powers there than they do on Main Street. Under the “border search” doctrine, CBP can inspect travelers and their belongings without a warrant and, in many cases, without individualized suspicion. That includes U.S. citizens. You must be allowed back in, but you can be delayed, questioned, and sent to secondary screening.

Those powers, though, don’t erase the Constitution. The First Amendment still bars the government from targeting people based on their viewpoints. That tension—broad authority to screen at the border versus protections for political speech—sits at the core of Piker’s claim and DHS’s denial. Was this routine? Or did the questions veer into viewpoint policing?

Courts have tried to draw lines. Judges have generally allowed “basic” border searches and wide‑ranging questions about travel, contacts, and purpose of trip. More invasive steps—like deep dives into electronic devices—tend to require higher justification. Policies have shifted as lawsuits mounted. In recent years, CBP has distinguished between “basic” and “advanced” device searches and, on paper, raised the bar for the latter.

But the questions Piker says he faced weren’t about luggage weight or customs declarations. They were about politics—his stance on Trump, Hamas, and current events. That’s why civil liberties lawyers pay attention to cases like this. Government agents can ask many things in secondary screening, yet when the subject turns to ideology, the First Amendment radar lights up.

The idea that political views could attract border scrutiny isn’t hypothetical. Over the last decade, travelers—including U.S. citizens, journalists, and activists—have reported being questioned or flagged in ways that seemed tied to their work or beliefs. In 2019, for example, news reports showed that DHS compiled a list of journalists and activists connected to coverage of the migrant caravan in Tijuana, prompting internal reviews. In 2017, Muhammad Ali Jr., a U.S. citizen, said he was asked about his religion at a Florida airport. CBP has repeatedly denied systemic targeting based on viewpoints and frames incidents as individual, lawful screenings.

There’s also the raw number of interactions. CBP conducts tens of thousands of secondary inspections and device searches at ports of entry each year. Most pass unnoticed. A few blow up—usually when they involve well‑known figures, reporters, or controversial political speech. That visibility forces a public accounting: what exactly counts as “routine,” and who decides?

Piker’s Global Entry status adds another twist. The program is marketed to low‑risk travelers who clear background checks and interviews. But it’s a privilege, not a right. CBP can still pull members for extra screening, and it can suspend or revoke membership. For people who sign up expecting predictability, being diverted into a political conversation with federal agents can feel like the floor falling out.

The timing didn’t help. Piker was bound for a campus appearance in a season already charged by Gaza protests, arrests, and heated fights over academic freedom. Universities have become a battleground for arguments over speech, safety, and protest rights. His detention, landing right then, naturally fed a narrative that critics of U.S. policy are being chilled—not just online, not just on campus, but at the border.

DHS insists it wasn’t political. That’s a serious claim too. If officers stuck to lawful screening and Piker read it as ideological, that’s a different story than agents digging for his views to punish him. The problem is proof. Secondary rooms don’t come with transcripts. Without a recording, the public gets clashing accounts and must infer motive from patterns and past cases.

There’s a practical angle here for anyone traveling with a public profile: your online life walks into the room with you. Agents can see news stories, social media clips, and viral moments that shape how they perceive risk. It’s lawful to ask about travel plans. It’s not lawful to punish speech. The line between those two can get blurry fast when your politics are your job.

Free speech experts often boil it down this way. The First Amendment protects you from government retaliation based on viewpoint. If questioning is clearly aimed at discouraging or penalizing lawful expression—especially core political speech—that’s a problem. If questions are tied to legitimate screening, that’s usually allowed. Because the stakes are high, agencies are supposed to train officers to steer clear of ideology and stick to objective risk factors.

On Monday, Piker told his viewers he thinks the point was deterrence—to scare people off criticizing U.S. policy on Gaza and the administration more broadly. He called it a “chilling effect.” That phrase has legal weight. Courts look at whether government actions are likely to dissuade a person of ordinary firmness from speaking. If yes, and if speech was the motive, that can violate the First Amendment even when there’s no arrest or fine.

For DHS, the institutional risk runs the other way. If officers stop asking hard questions at the border for fear of blowback, they argue, real threats can slip through. That’s why the agency defends broad discretion and calls incidents like this “routine.” It’s also why it bristles at claims of political policing: such accusations don’t just question an officer’s judgment—they question the agency’s legitimacy.

What would resolve this? Transparency helps. Agencies can log the categories of questions used in secondary screenings and publish aggregate data. Independent oversight bodies can audit sensitive cases. Clear guidance can remind officers that questions about ideology, voting, or peaceful political advocacy are out of bounds unless directly and specifically tied to a legitimate security concern.

Travelers, meanwhile, often ask what they can do. Civil liberties groups generally suggest a few basics. Know that, as a U.S. citizen, you must be allowed to reenter. You can ask if you’re being detained or if you’re free to go. You can ask for a supervisor. You can decline to share device passwords, though agents may hold your phone and you may face delays. If you think your rights were violated, you can file a complaint with DHS’s Traveler Redress Inquiry Program (DHS TRIP) or seek legal counsel.

- Secondary screening is legal, but prolonged questioning about lawful political beliefs raises First Amendment concerns.

- Global Entry reduces wait times; it doesn’t eliminate inspections or guarantee no secondary checks.

- U.S. citizens cannot be denied entry; refusing to unlock devices can lead to delays or device seizure, not exclusion.

- Document the interaction as soon as you leave the inspection area while details are fresh.

In real life, most travelers never see a secondary room. But the country sets its norms at the edge. If people believe speech can trigger extra scrutiny at the border, they self‑censor before they ever step off a plane. If, on the other hand, agents ignore bona fide warning signs to avoid controversy, that risks security. The balance is tricky, which is why cases like this draw outsized attention.

Piker’s experience won’t be the last test. The political climate is still hot. Gaza remains front and center. The election calendar keeps generating flashpoints. And platforms like Twitch have turned commentators into mainstream figures with audiences bigger than cable shows. When those figures travel, their speech rides with them through customs. Whether that speech becomes a subject—or stays off limits—will say a lot about where the country draws the line.

For now, we’re left with two stark versions. Piker says he was pressed on ideology to make an example of him. DHS says it was routine and lawful. The truth might sit in how “routine” is defined and whether the questions asked were necessary to assess a traveler’s risk or simply about what he believes. That’s the hinge—both legally and culturally—of the Hasan Piker detention story.